Expert Insights - Attachment, Caregiving and the Parental Brain

By Dr Pascal Vrticka, Centre for Brain Science, Department of Psychology, University of Essex, Colchester, UK

Infant attachment and the parental bond are closely linked. This article first examines the emergence of individual differences in these two dimensions and their significance. It then explores their neurobiological bases, focusing particularly on the parental brain. Finally, it discusses strategies that caregivers can use to promote the development of secure attachment in children.

Introduction

Starting during pregnancy and continuing across early infancy, a strong emotional bond begins to form between caregivers and their infants. This bond formation is made up of two elements. The first element is infant-directed behaviour towards caregivers, particularly proximity-seeking in times of need. If infants are hungry, cold, frightened, or ill, it is their natural tendency to seek physiological, emotional and psychological support from their caregivers. This first element is called attachment, unfolding as infants’ primary social survival strategy. The second element is caregivers’ response to infants’ attachment behaviour with the main aim to provide co-regulation. To provide efficient support and appropriate care, caregivers must develop an understanding of infants’ needs: their emotions, intentions and goals. This happens through bonding, characterized by feelings of love, affection, and compassion, the knowledge that infants require help and the motivation to provide it. What the above shows, is that attachment is always directed from a ‘care seeker’ towards a ‘care giver’, i.e., from infants towards caregivers. We should therefore always speak of infant-caregiver attachment but caregiver-infant bonding. A small but important difference [1].

Attachment and caregiving are tightly linked. On the one hand, infants’ proximity-seeking as part of their attachment behaviour usually triggers caregiving behaviour in the form of co-regulation The nature of caregivers’ co-regulation subsequently determines whether infants’ needs are met, and attachment behaviour can cease. Across many such infant-caregiver interactions, infants start building predictions and expectations about future infant-caregiver interactions and adjusting their attachment behaviour accordingly. That’s how individual differences in attachment – also known as attachment styles, classifications or orientations – emerge. On the other hand, caregivers’ behaviour is tightly linked to their own current attachment orientations and attachment history. Very often, parents’ own attachment orientations are reflected in their caregiving behaviour. Furthermore, if caregivers’ own attachment system is activated the way of providing care to their infants is affected. This is because attachment and caregiving are complimentary behaviours maintained by the same neurobiological systems that cannot optimally operate if employed simultaneously [2].

Individual Differences in Attachment and Caregiving

Individual differences in infants’ attachment orientations emerge as predictions and expectations about future interactions based on past ones. They reflect how efficient infants are in eliciting care and support, whether caregivers are available and readily respond to infants’ proximity-seeking attempts through co-regulation, and how helpful and appropriate caregivers’ co-regulation is. Crucially, we should not think of attachment orientations as either ‘good’ / ‘strong’ (i.e., secure) or ‘bad’ / ‘weak’ (i.e., insecure). Every infant (with very few exceptions) becomes attached to one or more caregivers. Because without attachment, infants cannot survive and thrive. Accordingly, all attachment orientations are meaningful and often necessary, because they emerge as specific responses to particular environmental demands. If caregivers are consistently unresponsive or unavailable for co-regulation, infants must adjust their attachment behaviour, become more self-sufficient and engage in more self-regulation. Conversely, if caregivers are inconsistently responsive and their availability for co-regulation unpredictable, it makes perfect sense for infants to intensify their support-seeking attempts to increase their chances of being heard [3].

But how do we measure infants’ attachment orientations, and how do we assess attachment and caregiving styles in caregivers? And how are these measures related to one another? Unfortunately, things become quite complicated at this point. Which is why most of the confusion about attachment terminology happens here. The main issue is that there is not one single measure of attachment but many different ones. What makes things even more difficult, is that all attachment measures come with their own underlying assumptions, derive attachment in many ways and use a variety of terms to refer to their outcomes.

Attachment in young infants is predominantly assessed using behavioural observations like the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) and thus reflects infants’ behaviour towards caregivers [4]. Conversely, in adults, attachment is measured either as part of semi-structured interviews like the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) reflecting the coherence and content of narratives regarding one’s attachment history [5], or with self-report questionnaires that reveal feelings and thoughts about current (often romantic) attachment relationships (e.g., the ECR-R [6]). Furthermore, while the SSP and AAI yield attachment categories, self-report questionnaires predominantly yield continuous scores.

Notwithstanding these important differences, all the attachment measures usually refer to attachment orientations as either secure (except in the AAI as autonomous) or insecure. That said, many different terms are used for insecure attachment: either avoidant/dismissing or anxious/ambivalent/resistant/preoccupied. What is more, while the SSP comprises a fourth child attachment orientation of disorganisation [7], the AAI can also classify adults as unresolved, and self-reports often attribute an adult insecure fearful(-avoidant) orientation. Although very often used interchangeably, disorganisation in children and unresolved or insecure fearful(-avoidant) attachment in adults are not the same. We therefore must be very careful with such attachment terminology [1].

There are additional measures of parent-infant bonding (which are, unfortunately, often referred to as ‘parent-infant attachment’) as well as caregiving. These are usually self-report questionnaires filled in by caregivers. While some of these questionnaires are similarly structured like attachment questionnaires (e.g., looking at deactivating versus hyperactivating caregiving styles that are related to avoidant versus anxious attachment orientations, respectively [8]), most have a completely different structure (e.g., assessing mothers’ emotional connection to her infant, including feelings of affection, pleasure, and engagement as part of caregiver-infant bonding [9]). This often makes it hard to directly link infant-parent attachment to parent-infant bonding.

Finally, none of the above-mentioned measures – including the SSP and AAI – yield clinical diagnoses or represent clinical disorders of any sort. There are two types of attachment disorders specifically manifested in infants that are listed in psychiatric diagnostic systems such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), i.e., reactive attachment disorder (RAD) and disinhibited social engagement disorder (DSED), but these are very rare in the general population and can only be diagnosed by trained clinical professionals as part of extensive assessments. Any reference to insecure or disorganised (infant) attachment as an attachment disorder is wrong and must be disregarded [7].

The Neurobiology of Attachment and Caregiving

During the last twenty years, a new research area specifically devoted to better understanding the neurobiology of human attachment has emerged: the social neuroscience of human attachment (SoNeAt [3]). What we can derive from the recently emerging knowledge for this chapter is twofold. First, we can appreciate how complex attachment’s neurobiology is and that there is much more to it than what is usually spoken about. And second, we can use this information to see how complex caregiving’s neurobiology is, too, and how strongly it is linked to the same neurobiological processes implicated in attachment.

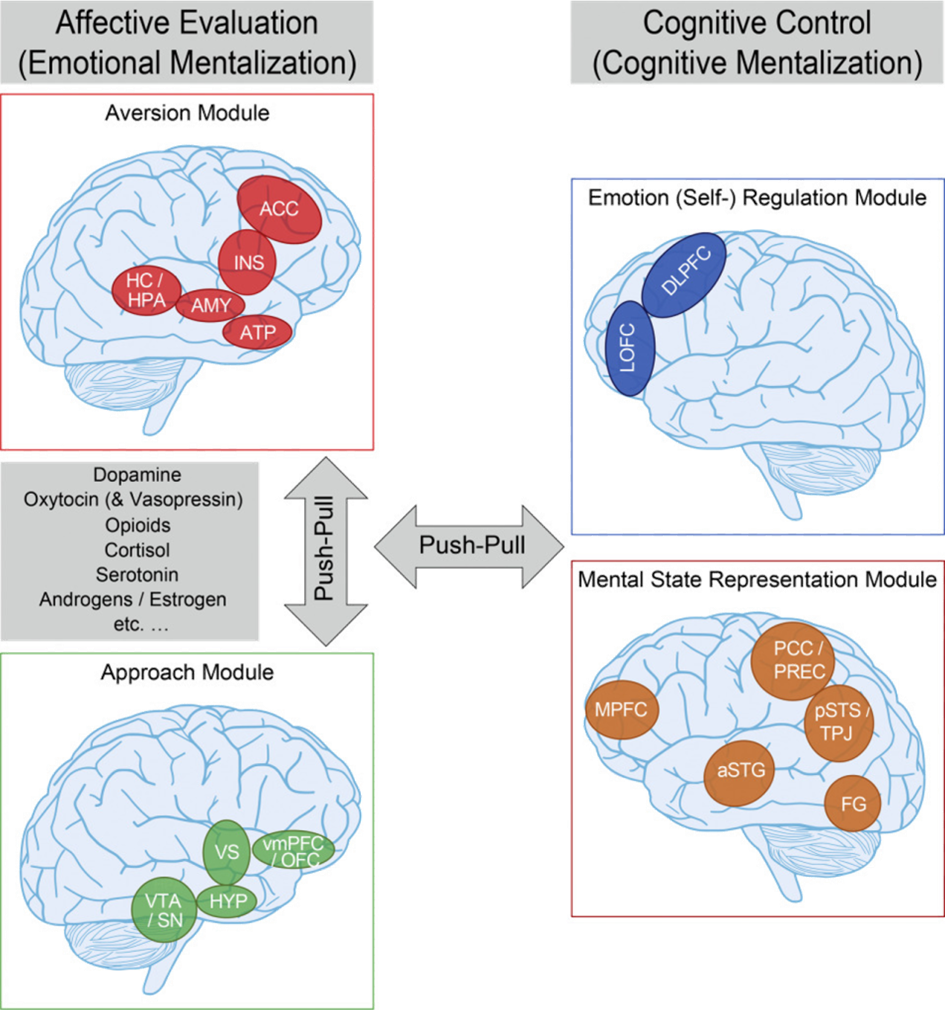

The latest integrations of SoNeAt data clearly show that attachment is everywhere in the brain. There is no single and specific ‘attachment brain area’, nor is there a single and specific ‘attachment neural circuit’. Attachment behaviour is very sophisticated, including many different elements that unfold in an elaborate sequence and require many different neural computations. We recently summarised these considerations in our Functional Neuro-Anatomical Model of Human Attachment (NAMA [10]). In the following, you can find a short accessible summary (see also [11]), including an illustration of NAMA in Figure 1.

Attachment behaviour is usually triggered by an event that upsets infants’ emotional and physiological balance. The first neurobiological process involved is thus usually one of threat detection and a fear response, telling the rest of the brain that something happened that needs immediate attention. We localise such neural computations in an extended ‘aversion module’ (or ‘threat-fear-pain module’) that processes the saliency of incoming information from various sources. What follows next is infants’ proximity-seeking behaviour, to let others know that they need help. This involves a pro-social motivation to establish closeness, which is maintained in another extended neural network what we call the ‘approach module’ (or ‘connection module’).

If proximity to others is established successfully, what happens next is co-regulation, which ultimately helps infants to develop self-soothing and self-regulation skills. This process works by up- or down-regulating activity within the aversion and approach modules through effective neural connections with another extended neural network that we call the ‘emotion regulation module’. In the case of successful co-regulation, the fear response can subside and infants’ physiology and emotional state return to balance. This calming down of the body and mind feels good and rewarding by itself. We therefore once more see increased activity in the approach module. Crucially, however, because the return to balance happens in the presence of supportive and caring others, their presence will be associated with positive feelings and reward in the approach module.

What individual differences in attachment reflect is a re-shaping of information processing and the neurobiological responses to it by means of ‘recalibrating’ the brain as a function of the environment.

Finally, if this sequence unfolds repeatedly and consistently, infants start forming expectations and predictions about future interactions that comprise mental representations about themselves (i.e., what can I do to get help?) and others (i.e., how available and helpful are others if I need them?). We localise such processes in a final extended neural network called ‘mental state representation module’ (or ‘self-other module’).

What the above clearly shows, is that attachment involves many different neural computations in several extended networks that are constantly talking to and exchanging information with one another. We should therefore no longer use outdated and oversimplified accounts of ‘right-brain versus left-brain’ processes and attachment being predominantly ‘right-brain based’ [12]. Furthermore, we should not refer to the ‘Triune Brain Model’ that segregates the human brain into three separate ‘reptile or lizard’, ‘mammalian’ and ‘human’ layers, with attachment mainly localised to the ‘mammalian’ layer. This model was flawed from the start and is not an accurate representation of human brain evolution, structure and function [13].

Now, how do individual differences in attachment emerge within the human brain? This happens through modifications of above-mentioned sequence of events and neural computations [3,9]. Depending on caregivers’ availability for co-regulation, infants learn to expect and predict the usefulness of different support-seeking as well as self- versus co-regulation strategies. Activity in the aversion, approach, regulation and mental state representation modules will in- or decrease, and the way and amount of communication between the modules will also change. If, for example, caregivers are mostly unavailable and unresponsive in times of need, the approach module will be less engaged, because there are fewer opportunities for associating the presence of others with feeling calm and soothed. Consequently, there will also be less proximity-seeking behaviour under distress and more self- than co-regulation. In turn, if caregivers’ availability and responsiveness is inconsistent and unpredictable, activity in the aversion module will be heightened not only to monitor caregivers’ whereabouts but also to intensify support-seeking behaviour so that caregivers are more likely to respond. Thus, what individual differences in attachment reflect is a re-shaping of information processing and the neurobiological responses to it by means of ‘recalibrating’ the brain as a function of the environment.

Now, how does this relate to caregiving and the parental brain? The key here is that attachment and caregiving are orchestrated by the same neurobiological circuits. The aversion, approach, emotion regulation and mental state representation modules are not attachment specific. They are also activated during caregiving (in fact, they are activated by many other things besides attachment and caregiving). Therefore, the ‘recalibration’ that happens to these neurobiological circuits as part of attachment interactions in early life will also show in parents’ caregiving responses later in life.

For example, when mothers were shown images of their own smiling and crying infants (as compared to unknown infants) in the fMRI scanner [14], mothers’ attachment representations as assessed with the AAI revealed an interesting pattern. While mothers with secure attachment representations showed high activity in reward-related areas (i.e., our ‘approach module’) both when seeing their smiling and crying infants, mothers with avoidant attachment representations did not. Furthermore, mothers with avoidant attachment representations had higher brain activity related to the processing of salient and predominantly negatively arousing information (i.e., in our ‘aversion module’) when seeing pictures of their own crying infants, indicating personal distress rather than a motivation to help.

Similar findings emerged from another study [15] that looked at mothers’ brain responses to infant videos as a function whether mothers’ caregiving styles were more or less attuned and intrusive. Mothers with a more attuned caregiving style showed higher activation in reward-related areas (i.e., our ‘approach module’) and better information exchange with areas part of our ‘emotion regulation’ and ‘mental state representation’ modules. Conversely, mothers with a more intrusive caregiving style showed higher activity in the amygdala (i.e., part of our ‘aversion module’) and less coordinated information exchange with the other neural modules.

Comparable results were also obtained by a study [16] that looked at changes in mothers’ brain structure pre versus post pregnancy as a function of mothers’ self-reported bonding towards their infants after birth. Not only were changes in brain structure particularly pronounced in brain areas important for inferring infants’ mental states, goals and intentions (i.e., our ‘mental state representation module’), but these changes were positively correlated with mothers’ self-reported quality of bonding and the absence of hostility toward their infants.

Finally, in a recent study of our own [17], we measured parent-child (age 5 years) interpersonal neural synchrony (INS) – the temporal alignment of parents’ and children’s brain activities – as well as parents’ attachment representations by means of the AAI. We found that those parent-child dyads in which mothers’ attachment representations were classified as insecure had higher INS in parts of our ‘emotion regulation module’, which may be a sign of more attention and regulation needed to maintain a good social interaction and relationship more generally.

When it comes to attachment and caregiving, there are no simple ‘parenting hacks’ that work for everybody and all the time.

Practical Implications and Recommendations

What can we learn from NAMA and our SoNeAt perspective on attachment and caregiving during pregnancy and early infancy? And are there any recommendations emerging from it for parents as well as individuals and institutions working with families? Together with the UK Charity Babygro, we summarise some of the implications in our Babygro Book for parents as part of CHATS [11].

CHATS comprises five elements: 1) How parents can become proficient at reading and responding to their infants’ cues and communications, 2) how attachment theory can help parents to understand their own attachment history and how it affects their caregiving, 3) how attachment theory can help parents to understand the formation and quality of infant-parent attachment, 4) how talking to infants can help building their understanding of the self and others as well as their emotion regulation skills, and 5) how all the above elements are affected by parent-infant synchrony – ‘turn-taking’ exchanges involving mutual eye contact, facial expressions, gestures and vocalisations.

Crucially, when it comes to attachment and caregiving, there are no simple ‘parenting hacks’ that work for everybody and all the time. Every caregiver-infant relationship, every interaction is different and unique. However, there are a few general recommendations that have been shown to improve caregiver-infant relationship quality and can therefore help infants to develop a secure attachment orientation and caregivers to use caregiving strategies that support the latter process.

For example, it does help for parents to reflect upon their own current attachment orientation and attachment history. As we have seen above, caregiving and attachment are tightly linked, and these tight associations can even be seen within caregivers’ brains.

In addition, research has shown that there are two reliable parent-based predictors of secure infant attachment emergence within the parent-infant relationship. The first one is parental sensitivity, i.e., parents’ ability to accurately perceive and appropriately respond to their infants’ signals and needs. The second one is parental reflective functioning, i.e., parents’ capacity to understand their own and their infants’ behavior in terms of underlying mental states and intentions, or, in other words, parents’ mentalizing abilities in the relationship with their children. Unsurprisingly, there is an intricate interplay between parental sensitivity and reflective functioning in addition to parents’ own attachment history [18].

Finally, it helps to know that parents do not need to be constantly present and always ‘on’. We know that for about 50-70% of the waking time of infants, parents and infants are not ‘in sync’ with one another [19]. We also know that there can be negative consequences to parents and children constantly being ‘tuned in’ to each other. It can increase relationship stress and raise the risk for insecure child attachment. Especially if it is associated with parental overstimulation or too high parental and child responsivity [20].

What should naturally happen instead, is for parents and infants to engage in a constant ‘social dance’ comprising attunements, mismatches and repairs. It is this flow of connection, disconnection and reconnection that offers children an ideal mixture of parental support and moderate, useful stress that helps growing children’s brains and fosters their attachment security. It suffices for caregivers to be ‘good enough’ – to be available when children need them rather than ‘always on’. What really counts is that the relationship functions well overall. That children can develop trust in their parents and that any mismatches, which naturally occur all the time, are successfully repaired.

This article was originally published in French at Sage-Femmes (Elsevier) in a special issue edited by Dr Jodi Pawluski. It is printed here with authorization from the author and publisher.

Published citation: Pascal Vrticka, L’attachement, les soins et le cerveau parental, Sages-Femmes, Volume 25, Issue 1, 2026, Pages 21-26, ISSN 1637-4088, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sagf.2025.11.007.

References

1. Verhage, M.L., Tharner, A., Duschinsky, R., Bosmans, G. and Fearon, R.M.P. (2023), Editorial Perspective: On the need for clarity about attachment terminology. J Child Psychol Psychiatr, 64: 839-843. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13675

2. Canterberry, M. and Gillath, O. (2012). Attachment and Caregiving. In The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Couples and Family Relationships (eds P. Noller and G.C. Karantzas). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444354119.ch14

3. White, L., Kungl, M., & Vrticka, P. (2023). Charting the social neuroscience of human attachment (SoNeAt). Attachment & Human Development, 25(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2023.2167777

4. Madigan, S., Fearon, R. M. P., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Duschinsky, R., Schuengel, C., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Ly, A., Cooke, J. E., Deneault, A.-A., Oosterman, M., & Verhage, M. L. (2023). The first 20,000 strange situation procedures: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 149(1-2), 99–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000388

5. Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Dagan, O., Cárcamo, R. A., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2024). Celebrating more than 26,000 adult attachment interviews: mapping the main adult attachment classifications on personal, social, and clinical status. Attachment & Human Development, 27(2), 191–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2024.2422045

6. Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item-response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350-365.

7. Granqvist, P., Sroufe, L. A., Dozier, M., Hesse, E., Steele, M., van Ijzendoorn, M., … Duschinsky, R. (2017). Disorganized attachment in infancy: a review of the phenomenon and its implications for clinicians and policy-makers. Attachment & Human Development, 19(6), 534–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2017.1354040

8. Colledani, D., Meneghini, A. M., Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2022). The Caregiving System Scale: Factor structure, gender invariance, and the contribution of attachment orientations. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 38(5), 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000673

9. Condon, J. & Corkindale, C. The assessment of parent-to-infant attachment: development of a self-report questionnaire instrument. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 16, 57–76 (1998).

10. Long M, Verbeke W, Ein-Dor T, Vrtička P. A functional neuro-anatomical model of human attachment (NAMA): Insights from first- and second-person social neuroscience. Cortex. 2020 May;126:281-321. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2020.01.010. Epub 2020 Jan 30. PMID: 32092496.

11. Babygro Book (2022). Published by Babygro. ISBN 978-1-3999-2823-6

12. So Happy Together: Deconstructing The Right Brain/Left Brain Myth. https://www.neuroscienceandpsychotherapy.com/post/right-brain-left-brain-myth. Retrieved 02.07.2025.

13. Cesario, J., Johnson, D. J., & Eisthen, H. L. (2020). Your Brain Is Not an Onion With a Tiny Reptile Inside. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(3), 255-260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420917687 (Original work published 2020)

14. Strathearn L, Fonagy P, Amico J, Montague PR. Adult attachment predicts maternal brain and oxytocin response to infant cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009 Dec;34(13):2655-66. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.103. Epub 2009 Aug 26. PMID: 19710635; PMCID: PMC3041266.

15. Atzil, S., Hendler, T. & Feldman, R. Specifying the Neurobiological Basis of Human Attachment: Brain, Hormones, and Behavior in Synchronous and Intrusive Mothers. Neuropsychopharmacol 36, 2603–2615 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2011.172

16. Hoekzema, E., Barba-Müller, E., Pozzobon, C. et al. Pregnancy leads to long-lasting changes in human brain structure. Nat Neurosci 20, 287–296 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4458

17. Nguyen T, Kungl MT, Hoehl S, White LO, Vrtička P. Visualizing the invisible tie: Linking parent-child neural synchrony to parents’ and children’s attachment representations. Dev Sci. 2024 Nov;27(6):e13504. doi: 10.1111/desc.13504. Epub 2024 Mar 24. Erratum in: Dev Sci. 2025 May;28(3):e70003. doi: 10.1111/desc.70003. PMID: 38523055.

18. Kungl, M.T., Gabler, S., White, L.O. et al. Precursors and Effects of Self-reported Parental Reflective Functioning: Links to Parental Attachment Representations and Behavioral Sensitivity. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01654-2

19. Tronick, E. Z., & Gianino, A. (1986). Interactive mismatch and repair: Challenges to the coping infant. Zero to Three, 6(3), 1–6.

20. Beebe B, Steele M. How does microanalysis of mother-infant communication inform maternal sensitivity and infant attachment? Attach Hum Dev. 2013;15(5-6):583-602. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2013.841050. PMID: 24299136; PMCID: PMC3855265.